A Garden of Desire and Delay

Rethinking Eden, Shame, and the Goodness of Being Known

Moses, who instructs all men with his celestial writings, He, the master of the Hebrews, has instructed us in his teaching— the Law, which constitutes a very treasure house of revelations, wherein is revealed the tale of the Garden— described by things visible, but glorious for what lies hidden, spoken of in few words, yet wondrous with its many plants. Response: Praise to Your righteousness which exalts those who prove victorious.

St. Ephrem The Syran, Hymns on Paradise, Hymn I:1

St. Ephrem the Syrian has a vision of Eden unlike anything I’ve ever heard before. For him, Eden—or Paradise, as he calls it—is a mountain. Actually, it’s the tallest mountain. He writes:

The summit of every mountain is lower than its summit, the crest of the Flood reached only its foothills.

Notice the capitalization?

He’s talking about The Flood. The one that destroyed the earth. The one that covered the whole world in water—and yet, Paradise stood above it.

Perhaps, to St. Ephrem, this is the summit from which the dove returned, olive branch in beak. Paradise was never worthy of destruction. Not even judgment could drown it.

The Tree of Life – Untouched Invitation

In the garden, we’re offered three trees: the Tree of Life, the Tree of Knowledge, and the fig tree. One of these receives the most attention and holds the center of the Eden story. But what if all three are worth our attention? What did they offer our first parents—and what do they still offer us?

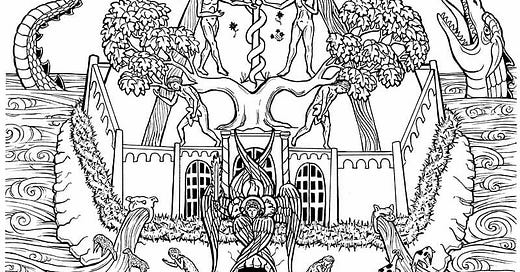

Of these, the most mysterious is the Tree of Life, which St. Ephrem places at the very summit of Paradise. For him, Eden is not a flat, gated meadow. It is a mountain—rounded, lush, surrounded by water, tiered with layers of creation. As you ascend, you pass through landscapes, lakes, and the animals of earth, until you reach the realm of the Sons of God—those redeemed and radiant in unity with their Maker.

And at the very top: the Tree of Life.

It is the tree most freely given, unlike the Tree of Knowledge, which came with condition. But there is a condition for this tree as well—unstated in Genesis, yet clear through Ephrem’s vision. Not a test of labor or suffering—Paradise is without toil—but of devotion. To reach the summit is not a matter of effort, but of faithfulness. Of singular desire. A heart trained not just to long for God, but to commune with Him.

And this tree—this Tree of Life—is not the one Adam and Eve eat from.

That doesn’t mean they weren’t in communion with God. They were. But they hadn’t yet reached the kind of intimacy that would place them in proximity to this tree. It wasn’t forbidden. It just wasn’t within reach. Not yet.

St. Ephrem puts it this way in his Hymns on Paradise, Hymn XII:

For God would not grant him the crown without some effort; He placed two crowns for Adam, for which he was to strive, two Trees to provide crowns if he were victorious. If only he had conquered just for a moment, he would have eaten the one and lived, eaten the other and gained knowledge; his life would have been protected from harm and his wisdom would have been unshakable.

God’s desire was always for us to receive both—Life and Knowledge. But in the right order, and in the right way. One received in communion, the other only safe once communion was secure.

The Tree of Knowledge of Good and Evil – The Ache and the Autonomy

Can we listen for what’s not being said?

Many of us grew up assuming the fruit itself was evil. Even if it wasn’t outright stated, it was implied. As if God placed something toxic in the middle of paradise—something beautiful, desirable, and utterly destructive.

As if a loving Father would set a trap.

But that’s not what the story says.

The tree is not called the Tree of Evil. It’s the Tree of Knowledge—of Good and Evil. A tree that offers wisdom. A tree that, in time, could have been a crown, not a curse.

The harm doesn’t come from the knowledge itself. It comes from the taking. From grasping what we’re not yet fit to carry. Plucked too soon, like the fruit in the story—knowledge without purpose, power without communion.

It’s not a sin of curiosity, but of rupture. The breaking of relationship.

The Fig Tree – Performance Born of Panic

Here’s the quiet one. If the Tree of Life is barely mentioned, the fig tree is almost invisible. But it’s there—waiting. Familiar. Named by our first parents. Eaten from. Freely given. And after the rupture, it’s where they return.

Not to taste. But to hide.

This is not reverence. It’s reflex.

Social psychologist Jack Katz puts it plainly: the fig leaves are performance. A way to blend into nature. To strive for normalcy without naming the wound. They take what is good and right and natural, and twist it into something unfitting of who they were—and who they now believe themselves to be.

Their silence before God isn’t just shame—it’s the first rupture in relationship. With God. With each other.

The Garden Rewritten in Wood

The story of Eden is communal and personal. A mythos and a mirror. A pattern of ascent and descent, fracture and return.

So it’s no surprise that another Garden comes.

The Second Garden – The Ache Revisited

He did not hide.

In Gethsemane, Christ doesn’t retreat—He presses in. He doesn’t isolate—He brings His companions, even if they cannot bear the moment. He doesn’t mask the ache—He names it:

“Father, if you are willing, remove this cup from me; yet, not my will but yours be done.”

And then He ascends the mount of Golgotha—and ascends the tree at its summit.

Not to cover shame, but to bear it.

Not to strip its leaves, but to become its fruit.

The Tree That Receives Him – All Three Trees Fulfilled

Christ, on the Cross, becomes the place where life is given. We eat of the Tree of Life only through Christ—the very Logos of God—and only by way of self-giving love.

This is not a bypass of suffering, but a pathway through it. Not an avoidance of ache, but its fulfillment.

In Golgotha’s tree, we see Knowledge revealed:

Goodness, in surrender.

Evil, in violence.

Humanity, in need.

And God, in mercy.

In this single tree, all three are answered:

Life is given.

Knowledge is revealed.

And fig-leaf shame is undone.

Even the fig tree is redeemed.

What was once stripped in panic now bears the fruit of peace. The tree that shaded our fear now shadows our healing. The leaves sewn in silence are answered by a body willingly broken.

When Jesus curses the fig tree in the Gospels, it’s not an act of cruelty—it’s a parable in motion. A mirror to our own instinct to perform instead of trust, to cover rather than confess. The fig tree, like us, could not bear what it was not ready to give. But on Golgotha, that symbol is transfigured.

The fig tree’s failure is undone—what once offered only cover, now offers Christ.

From Covering to Communion

This is where we return to Katz. He gives us language for something most of us feel but few of us name: performance isn’t vanity—it’s survival. The fig leaves weren’t rebellion. They were reflex.

Performance is not evil. But it’s not healing either.

Christ doesn’t scorn the instinct. He refuses it—and in doing so, He redeems it.

He meets our hiding with His own exposure.

Our silence with His Word.

Our panic with peace.

This is not a call to undress yourself on command.

It’s not a demand. It’s a mercy.

Christ’s redemption invites you

to stop pretending.

To give voice to the ache.

To bear your brokenness,

and be healed by His love.